by Vytautas Kuokštis, an Associate Professor at Vilnius University

The question of what determines political trust, or trust in political institutions, is a significant one. It addresses a foundational aspect of governance, and there is considerable scholarship on this matter. There exist two prevalent theories in this domain (Mishler and Rose, 2001). The first posits that institutional performance underlies trust. If a society experiences economic growth, low levels of corruption and crime, citizens are more likely to trust their political institutions (Wang, 2016). The second theory attributes political trust to cultural and sociological factors, primarily interpersonal trust. This perspective argues that increased trust amongst individuals leads to heightened trust in the government.

My research aligns more closely with the first theory but with a key modification. It is indisputable that the performance of government institutions plays a crucial role. Yet, this explanation faces two significant challenges. The empirical issue relates to the ambiguous relationship between indicators of good performance and political trust. The global landscape doesn’t clearly display patterns of correlation between these indicators and trust in political institutions. Neither is there a clear relationship over time. The United States, for instance, has witnessed considerable economic growth since the 1960s, yet trust in government has notably decreased.

The theoretical challenge centers on the concept of limited information. Consider a country experiencing economic growth and a decline in corruption. These indicators might be interpreted as positive, but it raises questions. Would another government have yielded better results? And to what extent can these improvements be attributed to government actions versus factors outside its control? Even expert analysts find themselves in disagreement over these matters, let alone the average layperson.

I propose that not merely the absolute performance matters, but also the relative performance. This proposition draws from the substantial body of research exploring the relationship between income and happiness. Studies indicate that as countries become wealthier, they do not necessarily become happier. However, there exists a relationship between income and happiness within a country on an individual level (Clark et al., 2008). One strong explanation is that people base their happiness not on absolute income but on their income relative to others – their reference group. An individual earning 50,000 euros per year may feel content if the national average income is 10,000 euros. However, the same individual could experience frustration in a scenario where the average income escalates to 100,000 euros, even if their purchasing power remains objectively the same.

Turning back to the connection between government performance and trust, I hypothesize that a country’s performance relative to a reference group of countries can be significant. For instance, in Lithuania, a comparison with Estonia is commonly drawn. Since the early 1990s, Estonia has been further along in implementing reforms, promoting economic growth, and reducing corruption. The relative performance gap between the two countries might explain why trust in political institutions in Lithuania has consistently been lower than in Estonia (although recently Lithuania has actually surpassed Estonia in terms of real GDP per capita, and it is curious to see whether that will have an impact on political trust).

My argument implies that the correlation between government performance measures and trust in political institutions should be stronger for countries that commonly compare themselves. Hypothetically, this relationship should be weaker globally but stronger within specific geographical regions. This is because people are likely to compare their situation with geographically closer countries.

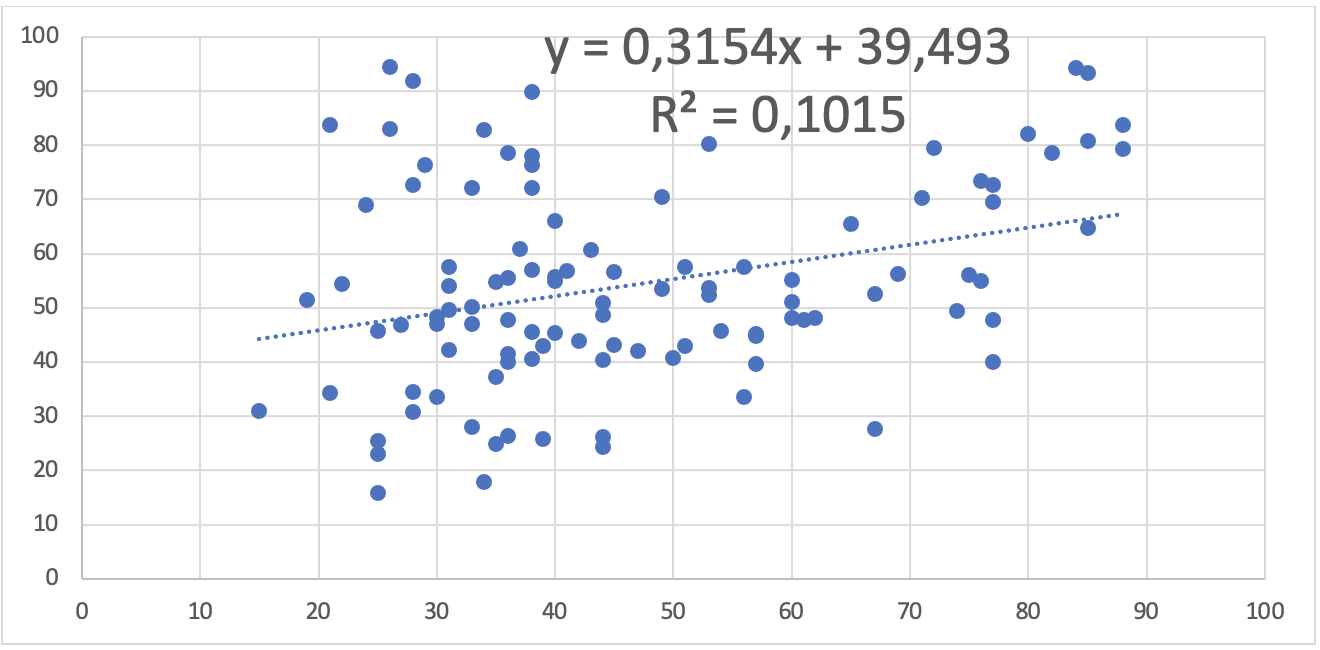

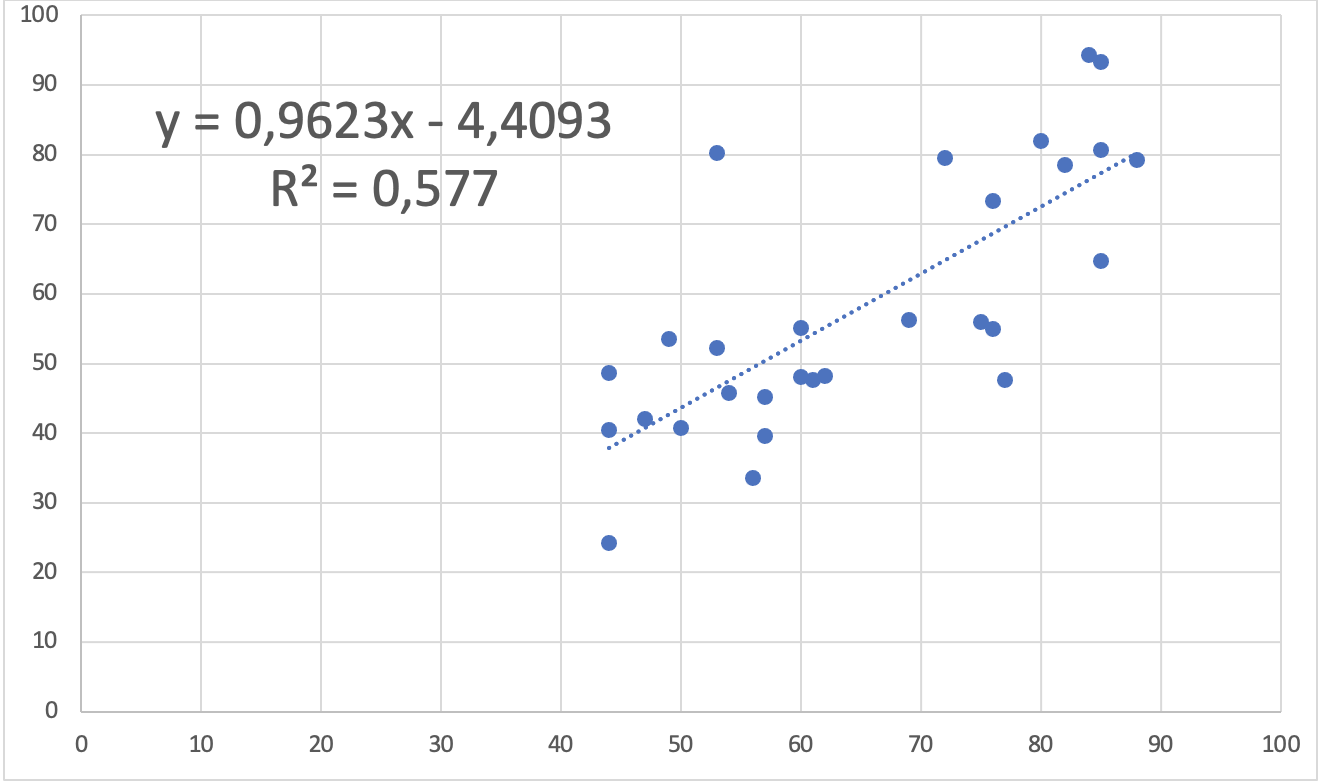

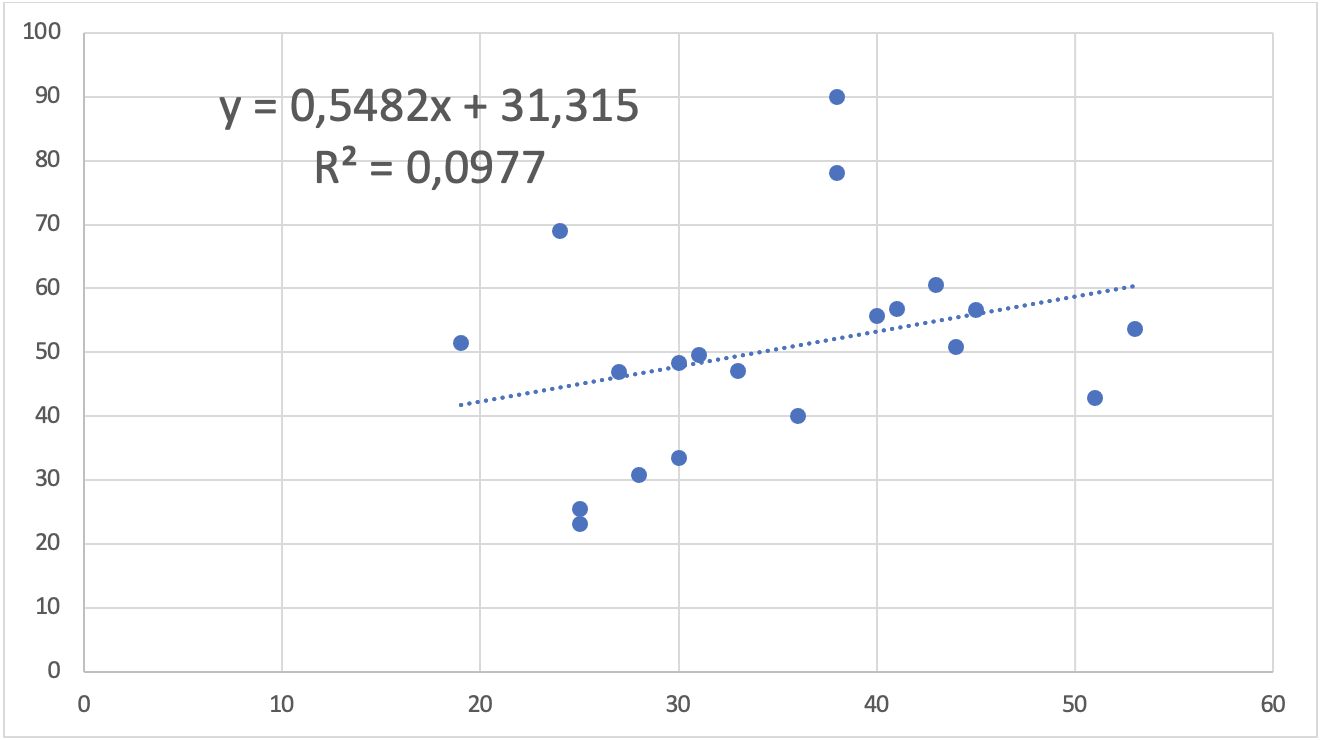

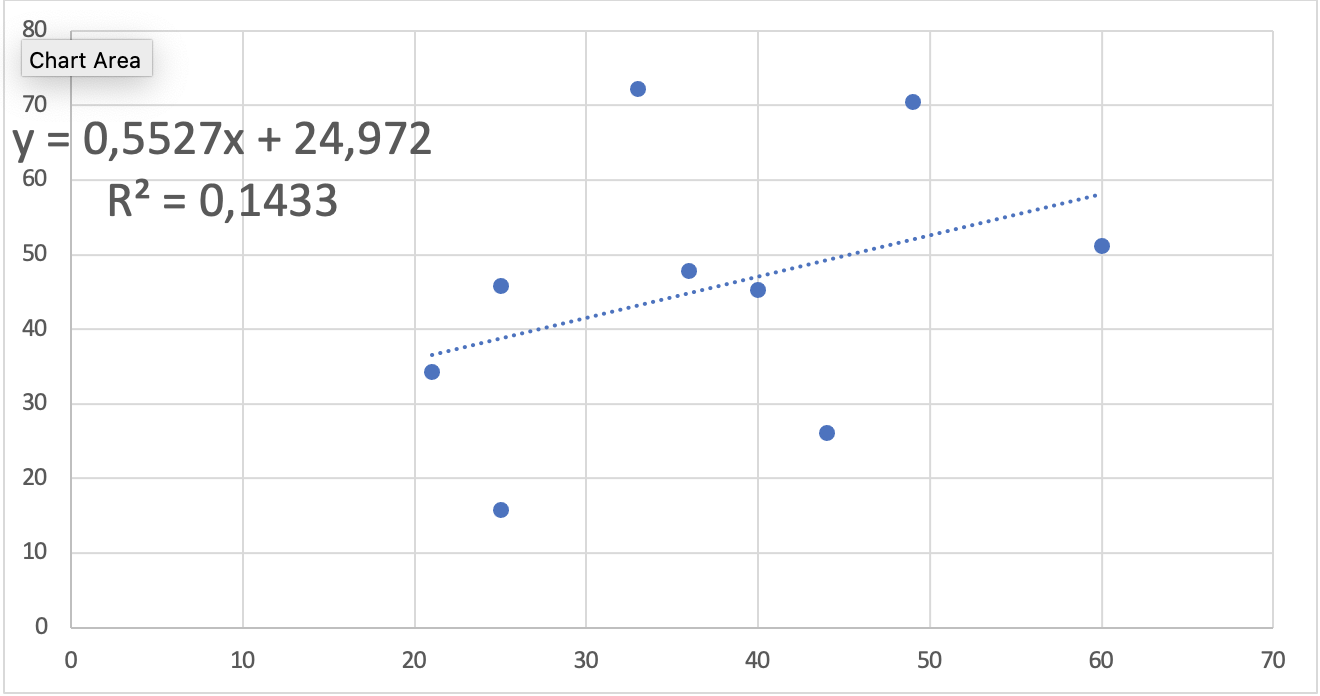

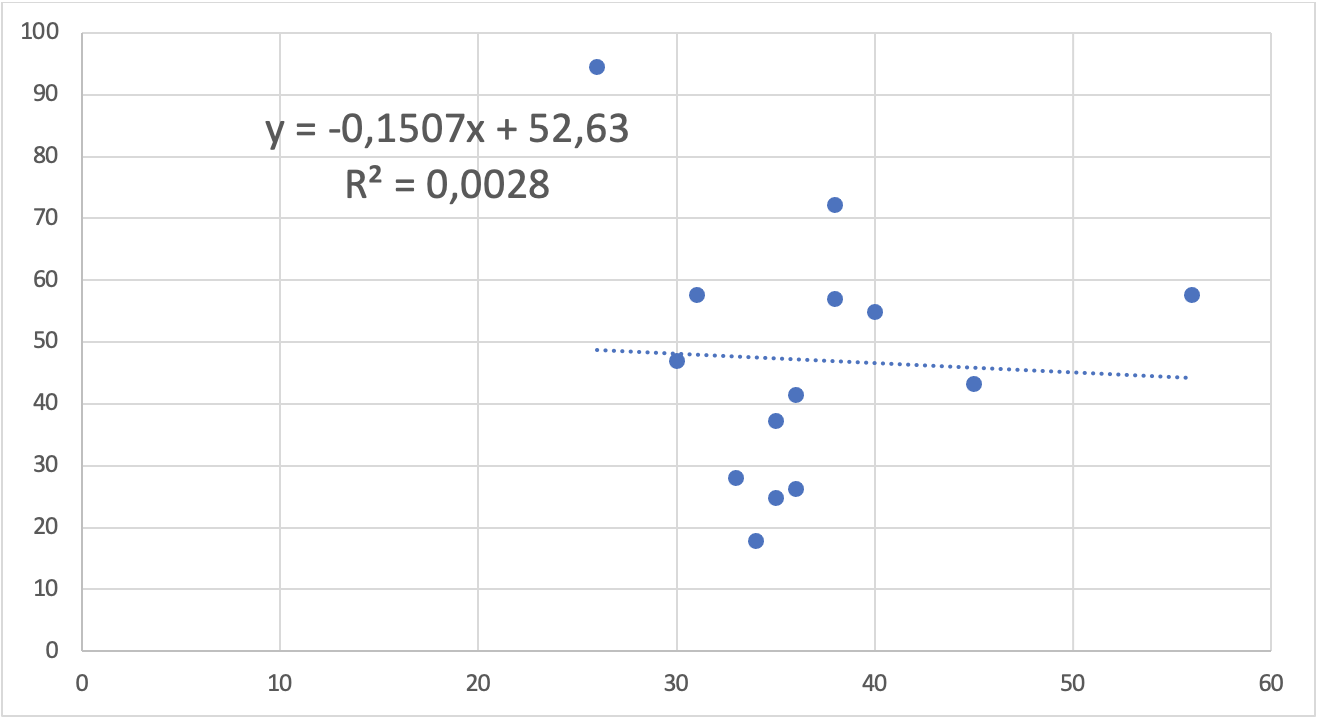

The figures below present a preliminary test of this hypothesis, showing the relationship between corruption perception and government trust globally and within various regions. These are rudimentary illustrations and should be taken as such but provide some supporting evidence. The relationship within most regions is stronger than at a global level. Regression coefficient sizes are larger in all regions but one. The correlation is particularly robust in the European Union, likely due to its high level of integration and various forms of exchange. The only exception is the Europe & Central Asia region, where there is virtually no relationship. However, if we exclude Uzbekistan, a deviant case with high corruption perception but also high trust, the relationship becomes positive and stronger than the global pattern.

Figure 1. Global relationship between corruption (Corruption perception index from Transparency International) and trust in the national government, represented on the X and Y axes, respectively. Data was sourced from World Bank, Transparency International, and Wellcome Global Monitor for 2020.

Figure 2. Relationship between corruption (Corruption perception index from Transparency International) and trust in the national government in the European Union, represented on the X and Y axes, respectively. Data sourced from World Bank, Transparency International, and Wellcome Global Monitor for the year 2020.

Figure 3. Relationship between corruption (Corruption perception index from Transparency International) and trust in the national government in selected African countries, represented on the X and Y axes, respectively. Data was sourced from World Bank, Transparency International, and Wellcome Global Monitor for 2020.

Figure 4. Relationship between corruption (Corruption perception index from Transparency International) and trust in the national government in selected MENA countries, represented on the X and Y axes, respectively. Data sourced from World Bank, Transparency International, and Wellcome Global Monitor for the year 2020.

Figure 5. Relationship between corruption (Corruption perception index from Transparency International) and trust in the national government in selected countries of Europe & Central Asia region, represented on the X and Y axes, respectively. Data sourced from World Bank, Transparency International, and Wellcome Global Monitor for the year 2020.

References

Clark, A.E., Frijters, P. and Shields, M.A., 2008. Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), pp.95-144.

Mishler, W. and Rose, R., 2001. What are the origins of political trust? Testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies. Comparative political studies, 34(1), pp.30-62.

Wang, C.H., 2016. Government performance, corruption, and political trust in East Asia. Social science quarterly, 97(2), pp.211-231.