By Dr. Azamat Mukhtarov (Kurultai Research and Consulting)

A Journey Between Continents — and Concepts

When I first arrived in Istanbul in February 2024, the city greeted me with a mosaic of sounds, sights, and histories. The call to prayer mingled with the hum of ferries crossing the Bosphorus, symbolically linking Asia and Europe — and, in a way, mirroring my own academic journey between different worlds of thought.

I was in Istanbul for my research secondment at Marmara University, undertaken as part of the MOCCA Project (Multilevel Orders of Corruption in Central Asia), funded by the European Commission under Horizon Europe’s Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (101085855).

My secondment was divided into two phases — 1 February to 29 February 2024 and 4 May 2024 to 13 May 2025 — allowing me to weave sustained engagement with the city’s intellectual life into the broader research agenda of the MOCCA network.

These periods were not merely about academic exchange; they became a space for personal reflection on how anti-corruption policy, social norms, and morality intersect in contemporary Uzbekistan — the core focus of my ongoing research project.

Istanbul: A Laboratory of Cultural Encounters

Few cities in the world embody hybridity as vividly as Istanbul. Every street, mosque, and café seems to contain overlapping histories — Byzantine and Ottoman, Islamic and secular, traditional and modern.

In that sense, Istanbul felt like a natural setting to explore questions of moral pluralism and legal hybridity — issues central to understanding corruption and anti-corruption in Central Asia.

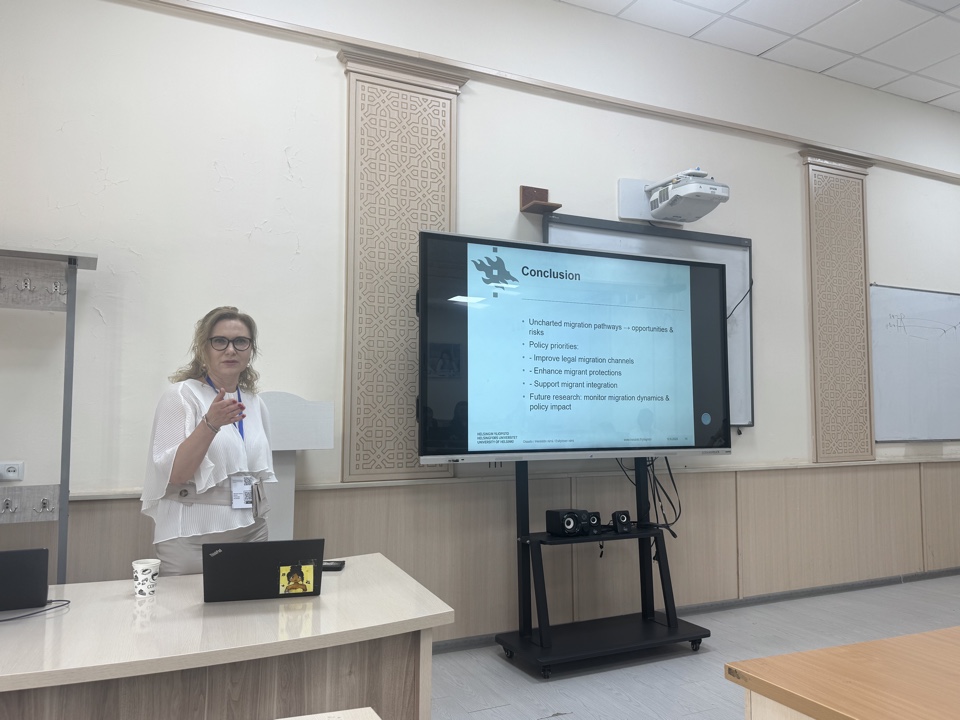

At Marmara University’s Department of Political Science, I found a welcoming and stimulating academic home. My host colleagues were incredibly generous with their time and insights. The seminars I delivered there — particularly on the “Nexus Between Anti-Corruption Measures, Social Norms, and Morality in Uzbekistan” — attracted both graduate students and faculty members.

Our discussions often revolved around how anti-corruption strategies imported from global frameworks, though well-intentioned, sometimes fail to resonate with local moral universes. For instance, a “bribe” from a Western legal perspective may, in a Central Asian context, overlap with deeply rooted social obligations of gift-giving, reciprocity, and solidarity. These distinctions, while subtle, are essential to understanding why corruption persists — and why simplistic legalistic solutions often falter.

The MOCCA Framework: Studying Corruption Beyond the Law

The MOCCA Project, under the leadership of Prof. Rustamjon Urinboyev (Lund University) has provided an interdisciplinary platform for scholars to study corruption not as a pathology of governance but as a social phenomenon intertwined with norms, values, and moral reasoning.

In February 2024, I took part in the MOCCA Methods Workshop held in Istanbul. This event brought together an inspiring range of scholars from across Europe and Central Asia. Sessions by MOCCA researchers encouraged us to rethink the very foundations of social research — from methodological decolonization to ethnographic engagement with “difficult-to-access” social groups. For me, these discussions were transformative. They underscored the importance of listening carefully to everyday moral logics — those unwritten rules that guide people’s behavior long before any formal law enters the picture.

Research Focus: Anti-Corruption, Social Norms, and Morality in Uzbekistan

My research project, provisionally titled “Anti-Corruption, Social Norms and Morality in Uzbekistan”, examines how anti-corruption efforts intersect with the moral economies and everyday ethics of Uzbek society.

Drawing on field insights and theoretical work developed within MOCCA — especially the ethnographic studies by Rustamjon Urinboyev and Måns Svensson on corruption and everyday life— I explore how people in Uzbekistan navigate a field of overlapping normative orders: the formal law of the state, the moral codes of Islam, and the expectations of kinship, family, and community (mahalla).

While international organizations define corruption as the “abuse of public office for private gain,” this definition often clashes with local understandings of morality and obligation. In many contexts, social survival depends not on rejecting informal exchanges but on participating in them — as acts of generosity, reciprocity, or moral duty.

This reality poses a profound challenge to anti-corruption reforms: how can legal systems combat corruption without undermining the moral and social bonds that hold communities together?

My ongoing work argues that genuine reform must integrate the moral grammar of society — rather than impose external models that ignore lived experience. Understanding corruption in Uzbekistan, therefore, means understanding the moral life of informality.

The Broader Intellectual Context

My participation in the MOCCA Mid-Term Conference (Lund, 6–8 May 2025) reinforced this interdisciplinary dialogue. The conference gathered leading researchers from across Central Asia, offering comparative insights into the cultural dimensions of corruption — from gift-giving practices in Uzbekistan to informal governance structures in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Hearing these diverse perspectives deepened my conviction that social norms and morality are not peripheral but central to understanding governance in post-Soviet societies.

This intellectual environment has also shaped my forthcoming book chapter, to appear in an edited volume within the Palgrave IPE Series, co-edited by Prof. Ruziev and Prof. Urinboyev. The chapter builds on MOCCA’s commitment to exploring corruption as a multilevel order — one that spans the law, the state, and the moral lives of ordinary people.

Life in Istanbul: Between the Academic and the Everyday

Beyond conferences and research meetings, daily life in Istanbul offered an education of its own.

Walking through the narrow streets of Kadıköy or crossing the Galata Bridge at sunset, I often thought about how cities, like societies, are built on invisible moral compacts — shared understandings of trust, respect, and reciprocity.

Istanbul reminded me that anti-corruption research is not only about analyzing systems but also about recognizing the humanity that underlies those systems. Whether in a café conversation, a public lecture, or a casual discussion with colleagues, I found that ideas about morality and integrity are living, evolving concepts — constantly negotiated between tradition and modernity.

The hospitality and collegiality of Turkish scholars, especially Professor Erhan Dogan created an atmosphere of intellectual openness that made my research both productive and personally enriching.

Knowledge Transfer and Future Collaboration

As part of my secondment’s dissemination activities, I shared the methodological insights I gained in Istanbul with my colleagues at Kurultai Research and Consulting, contributing to a practical workshop on integrating ethnographic methods into policy-oriented anti-corruption research.

These exchanges have already inspired new collaborations — including plans for joint seminars with Marmara University and the wider MOCCA network on the moral foundations of governance reform in Central Asia.

I am also exploring ways to engage with policy communities in Uzbekistan, helping bridge the gap between academic research and public discourse on anti-corruption.

Reflections and Gratitude

Looking back, my Istanbul secondment was more than an academic assignment — it was a journey of intellectual transformation.

The city’s layered history, the generosity of my hosts, and the MOCCA project’s interdisciplinary spirit together offered a unique vantage point from which to reconsider the relationship between law, morality, and social order.

I return from Istanbul with a renewed sense of purpose: to contribute to a more nuanced, culturally grounded understanding of corruption in Uzbekistan — one that acknowledges not only the legal frameworks but also the moral worlds in which people live.

Concluding Thought

Corruption, when viewed only through the prism of law, appears as a deviation to be eradicated. But when seen through the eyes of anthropology, sociology, and moral philosophy, it reveals a more complex truth: it is also a reflection of how communities organize trust, obligation, and survival.

In Istanbul, standing on the bridge between continents, I was reminded that research, too, must learn to bridge worlds — between law and morality, formality and informality, and the local and the global.

Only by doing so can we move closer to understanding, and ultimately transforming, the moral landscapes that sustain corruption — and the possibilities for integrity — in societies like Uzbekistan.

Comments