by Tolibjon Mustafoev, PhD candidate at Lund University

For the last few decades, Uzbekistan has been a popular research destination for many scholars studying authoritarian regimes. Indeed, the first president of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov, had been in power from the first days of independence in 1991 until September 2016. Karimov was known for his policies on closed economy, high bureaucracy, centralised control over business climate and civil society, strong state security and brutal foreign politics. As the guardian mentioned, Karimov ‘ruled with the iron feast’ for twenty-five years. But then when Mirziyoyev took the lead, the Uzbek nation experienced some democratic shifts in many areas including the economy (ex. currency exchange became liberal and the Central Bank’s authority space for dictating the rules in the banking sector was shrunk)), public services (initiation of Single Window State Service Center), taxation and business. The most important changes occurred after the nationwide referendum for the new version of the constitution of Uzbekistan on 30 April 2023. The new constitution emphasizes that Uzbekistan is a social state and that it needs to move towards the establishment of a welfare state and provide equal access to social security for citizens. However, Uzbek authorities had been preparing for new constitutional amendments long before their adoption. Starting from 2021 citizens were categorized into different segments based on their economic conditions by taking into account the gender and age dimensions. As a result, unemployed youth were categorised as ‘ununited youth’ and a special register named ‘Youth Notebook’ was created, unemployed and economically disadvantaged women were registered in so-called ‘Iron Notebooks’. Each category of citizens falls under special state programmes that provide access to low-interest loans, free equipment to start mini-scale businesses and many more.

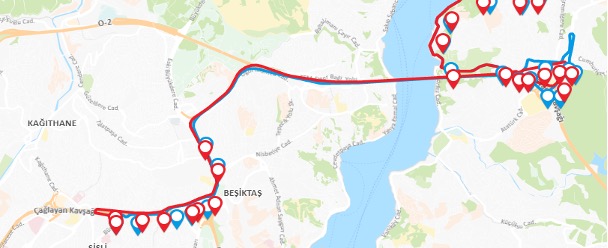

Hence, in the case of Uzbekistan, we can witness how a state shifted its focus from state security to social development in a matter of less than five years. In this blog post, I try to briefly provide analyses of policy developments directed at establishing a welfare state and eradicating poverty in Uzbekistan. My motivation to write this blog post appeared during my secondment from the MOCCA project to Uzbekistan in 2024. During the secondment period, I collaborated with two professors from the University of Zurich, Peter Finke and Meltem Sancak and three of us organised joined fieldwork in rural areas of Uzbekistan to collect data on the implementation of poverty reduction policies and state programmes in real-life. During the data collection process, we interviewed representatives of khokimlar (mayors), specifically, khokim yordamchilari (assistants to khokimlar), citizens who participated in state programmes for eradicating poverty and citizens who decided not to be engaged with state programmes regardless of their harsh economic conditions and poor living standards. Such a diversity of respondents helped us to understand the ongoing reformatory agenda in Uzbekistan from many perspectives such as from the top-down (during the interviews with khokim yordamchilari) and from the bottom-up (vulnerable citizens). This blog post mainly focuses on policy analyses by referring to only some of the fieldwork data, whereas this topic is planned to be covered by a larger research scope for further publication as an article.

To start with, historically, Uzbekistan’s legislative efforts to eradicate poverty from its Independence Day on 31st August 1991 to 2025 can be analyzed by looking at key reforms, policies, and actions undertaken by the government to address economic disparities, social inequalities, and poverty alleviation during that period. In this blog post, I analyze policy developments on eradicating poverty and establishing social welfare in Uzbekistan by looking into four different periods and by linking the latest reformatory agendas to the cases and experiences of private persons who participated in our fieldwork as respondents:

Transition Period and Early Reforms (1991–2000)

When Uzbekistan declared its independence from the Soviet Union, its citizens and institutions experienced economic instability, a collapse of state subsidies, and high inflation. Due to the fact that Uzbekistan inherited a highly centralized and inefficient economy, the legal and institutional framework needed to be restructured to address poverty, but legislative actions during this period were limited, focusing primarily on maintaining state control and stabilizing the economy. A year after its independence, the Constitution of Uzbekistan was adopted and it enshrined fundamental human rights, including the right to work and access to social security. Although the Constitution recognized social welfare as an important goal, the legal structure for addressing poverty was not fully developed at this stage. Although some social security nets such as child benefits and pensions were introduced, they were limited in scope and lacked effectiveness due to economic constraints. During this period, from an economic perspective, the Government of Uzbekistan mostly concentrated its focus on reforms to Land Law which aimed at the redistribution of land to improve agricultural productivity and reduce rural poverty (Melnikovová, 2016). However, new land policies remained a challenging task to be implemented due to a shortage of local state funds and poor infrastructure. Moreover, this period included a mass privatization of state enterprises which resulted in uneven distribution of wealth and assets among citizens (Rakhman Khan, 1996).

Strengthening Social Programs and Economic Development (2000–2010)

The 2000s marked a period of gradual economic growth in Uzbekistan, accompanied by a stronger emphasis on poverty alleviation through targeted social policies. The government began to focus more systematically on addressing poverty through legal reforms and institutional adjustments. After a series of consultations with international organizations such as the United Nations (UN) International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, the government of Uzbekistan adopted a Poverty Reduction Strategy in 2005 aimed at increasing economic growth, diversifying the economy, and reducing regional and social disparities (IMF, 2005). One of the interesting facts about the strategy is that it did not consider employment as a guarantee against poverty, which is not the case for how the current government of Uzbekistan frames the concept of employment which I reflect later in the text. This entire strategy was addressed and evaluated by the International Monetary Fund in its report from 2015. In its report, the IMF highlighted the possibility of accelerating economic growth only in the case of sustained macroeconomic stability (2005). Moreover, the IMF report highlights the necessity for the improvement of the credit policy through 2005 by expansion of the incidence of market mechanisms of the distribution of credit resources and creation of a full-scale money market and liberalization of commercial banks’ interest rates. Uzbekistan reflected on some of the recommendations of the IMF on social programmes and rural area development recommendation. Also, a new legislation ‘Law on Microcredit Institutions’ adopted on September 20, 2006, facilitated access to financial resources for small-scale entrepreneurs, particularly in rural areas. Microfinance institutions became an important tool for poverty alleviation, enabling small businesses and farmers to invest in income-generating activities. However, microfinance organizations attracted a large number of shareholders and private investment creating financial challenges for the banking sector of Uzbekistan. Moreover, the absence of intensive competition in the market of microfinance organizations caused a cross-indebtedness among the population in Uzbekistan (Sabi, 2013).

Comprehensive Reforms and International Cooperation (2010–2020)

The policies on the economy became less liberal in the early 2010s due to the introduction of heavy state control over private credit organizations creating bureaucratic challenges for private credit unions to keep providing financial services to people in rural areas. Adoption of the decision of the Chairman of the Central Bank of Uzbekistan ‘On the Approval of the Regulation on Requirements for the Credit Policy of Credit Associations’ from 24 March 2011 ceased the further development of credit unions in the state. Then, almost a decade after the IMF 2005 report on the Poverty Reduction Strategy, Uzbekistan puts forward the agenda for mass reform of the banking sector which becomes the first big step towards liberalizing the economy. That step was taken under the rule of new president Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who came to power in 2016. His administration prioritised a shift towards more inclusive economic growth, deeper legal reforms, and engagement with international organizations on poverty reduction.

During the first years of new leadership, Uzbekistan launched its National Development Strategy for 2017-2021, which prioritized the reduction of poverty, improving living standards, creating jobs, and ensuring social inclusion. The strategy included legal reforms aimed at enhancing the welfare system, education, and healthcare. In addition, the decision of the Cabinet of Ministers of Uzbekistan from 5 April 2018 ‘On the approval of the regulation on the Procedure for Establishing the List of Lone Elderly and Disabled persons in Need of Care’ expanded the scope of social assistance, focusing on most vulnerable groups of people. On one hand, the above-mentioned reforms were designed to better target poverty-stricken areas by establishing a centralised control over the policy implementation on providing equal access to social security. On another hand, those reforms established a new culture in government which is a categorisation of people living based on their social well-being (Cabinet of Ministers of Uzbekistan, 2021). In a later stage of the reformatory agenda of Uzbekistan, we can observe the initiation of the creation of many other categories such as Yoshlar Daftari(Youths’ Notebook)- a database of unemployed youth, Ayollar Daftari (Women’s Notebook)- database on identifying, eliminating and monitoring the problems of unemployed women who have the need and desire for social, economic, legal, psychological support, knowledge and vocational training; Temir Daftar (Iron Notebook)- a database for registering, identifying, eliminating, and monitoring the problems of families with difficult social and living conditions.

One of our respondents who falls under the category of women living under poor economic conditions from rural Bukhara claims that she was listed to one of the mentioned registers. However, she is not very much aware of the exact type of register where she was listed by her mahalla representative (formal institution, a type of residential community association, subsidised and funded by state and informal contributions of mahalla residents). In 2020 she was promised by the mahalla to be provided with a sewing machine for free. According to our respondent, she was expecting the promise to be kept and accordingly she planned to establish a mini sewing business at home. However, our respondent never received any sewing machine, instead her mahalla offered our respondent a time cash payment of 500,000 sums equivalent to 45 USD. Our respondent refused the offer and conducted her own little investigation. It turns out that sewing machines arrived at her mahalla and were distributed to some family members, close friends and two other ladies who offered 100 USD bribe to the local mahalla representative. Then our respondent shared that she lost hope in the local government representatives and local khokim yordamchisi who was in charge of implementation of the state programmes on poverty eradication directly in the district.

However, another respondent from the neighbouring district with the previously mentioned respondent, had a very positive experience in the beginning of reforms. Our second respondent had a big land in his neighbourhood which he used for producing vegetables to supply the local market demands. In 2019 he had a chance to receive almost half a million USD loan with a very low interest rate to grow tomatoes and cucumbers for export purposes. Considering the fact that our respondent had no experience in loan taking and managing a business on such a large scale, he failed to meet the requirements of the loan and almost went bankrupt. Later on, he changed his business plan from producing tomatoes to producing strawberries. The bank providing the loan had no problems with such a change in the business plan. Our respondent shares that the bank only cares about the loan interest to be paid on time no matter what. Currently, our respondent is still paying his loan which is in foreign currency, USD, and has not been making any profit so far. However, he claims that this loan enabled him to upgrade his living conditions to a certain extent and to explore new business dimensions.

Continued Reform and Sustainable Development? (2020–2025)

As of the 2020s, the government’s approach to poverty eradication was increasingly focused on the long term. That fact is visible from various policy initiations, for example, Presidential Decree No. PP-436 validating the Program on the transition to a “green” economy and ensuring “green” growth in the Republic of Uzbekistan until 2030. Legal measures encouraged the growth of the digital economy and entrepreneurship, especially in underdeveloped areas. This included support for start-ups and small-scale businesses such as sewing, cooking, farming and poultry farming which provided new job opportunities, particularly for youth and women. Nonetheless, continued reforms focused on enhancing access to healthcare and education through the expansion of public-private partnerships and increasing government funding in these sectors. These sectors were viewed as essential to breaking the cycle of poverty, as they directly contribute to human capital development. Indeed, the continued reformatory agenda of Uzbekistan in poverty reduction and social protection in 2020-2025 is better observable in two specific sectors: private business and education.

Most of our respondents claim that they started truly feeling the reforms after the ‘Mahallabay’ system of public service initiation. This system is initiated by the Cabinet of Ministers and considers the penetration of state reforms in each mahalla. Almost all local public servants from all public agencies started travelling within their assigned districts and visiting all mahallas to study the social issues and economic struggles. As a result, many individuals were registered in different registry ‘Notebooks’ for further assistance. Indeed, after analyzing the rate of poverty in rural areas, local authorities started enforcing the ‘chicken economy’ introduced by President Mirziyoyev earlier in 2017. During Mirziyoyev’s visit to Karakalpakstan on January 21, the President recommended to local people living in rural areas to engage in poultry farming in order to improve the living conditions of low-income families, he said: “Across our republic, especially in Karakalpakstan, every household living in the village is obliged to feed 100 chickens. 100 chickens produce at least 50 eggs a day. If you eat 10 of them yourself and sell 40 eggs every day, you will not be a low-income family. This is the stability of our tomorrow’s economy. “said Shavkat Mirziyoyev (BBC, 2017).

To understand the impact of reforms in rural areas, in July 2024 we organized a comparative study of two mahallas. One mahalla had many people who received micro-low loans through khokim yordamchilari, and the second mahalla had zero people who received a loan for chicken, but instead, the second mahalla people had many micro-loans for mini-truck vehicles and welding shops. Many people from the first mahalla failed to pay back their debts to banks because their chickens died because of poor fencing conditions and sickness. However, there were some successful cases of chicken farming, which required some additional private investment from loan takers. The second mahalla could be framed as a success case because except for one person all people who used the micro-credits provided by the state for poverty eradication could upgrade their living standards. Our preliminary analyses on why the second mahalla had a successful experience of implementation of recent reforms are linked with the competence of khokim yordamchisi who knows the local people’s skills and social settings and knows how to filter the reforms and provides access to local people only to the reforms with higher chances of social benefit rather than desperately using all the financial opportunities provided by the central government.

As concluding remarks, Uzbekistan’s legislative approach to poverty eradication evolved from reactive and minimal interventions in the early years of independence (1991–2000) to a more comprehensive, multi-faceted approach in the 2000s and 2010s. In the 2020s, the focus shifted toward long-term sustainable development, incorporating social, economic, and environmental factors into the poverty reduction strategy. However, challenges remain, including income inequality, rural poverty, and the need for more effective targeting of welfare programs.

Ongoing reforms, bolstered by international cooperation and a more open approach to market economy principles, aim to reduce poverty and inequality while promoting inclusive growth. The challenge for Uzbekistan in the coming years will be to implement these legal measures effectively and ensure that the benefits of economic growth reach all segments of society.

Reference list:

An assessment of the social protection system in Uzbekistan Based on the Core Diagnostic instrument (CODI). (2020). ILO, UNICEF, and the World Bank. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@europe/@ro-geneva/@sro-moscow/documents/publication/wcms_760153.pdf

Azizur Rahman Khan, “The Transition to a Market Economy in Agriculture,” in Keith Griffin, ed., Social Policy and Economic Transformation in Uzbekistan, Geneva: ILO, 1996.

Decision of the cabinet of Ministers #637 dated from 12 October 2021 ‘On Approving the Regulation on the Procedure for Allocating Unsecured Loans for the Construction of Additional Housing in the Individual Households of Children of Families Included in the “Iron Notebook” and “Women’s Notebook ” and Newly Married Young People Entered in the “Youth Notebook”’. https://lex.uz/docs/-5676240

Decision of the Cabinet of Ministers of Uzbekistan from 5 April 2018 ‘On the approval of the regulation on the Procedure for Establishing the List of Lone Elderly and Disabled persons in Need of Care’ https://lex.uz/docs/-4870034

Decree of the President of Uzbekistan No. PP-436 dated 2 December 2022 on ‘ Validating the Program on the Transition to a ‘Green’ Economy and Ensuring ‘Green’ Growth in the Republic of Uzbekistan until 2030’. Available at https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/uzb219338.pdf

International Monetary Fund. (2005). Republic of Uzbekistan: Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper. IMF Staff Country Reports, 05(160), i. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781451839814.002

“Karimov rules with an iron fist.” (2005, May 16). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/may/17/theeditorpressreview

Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan “About non-bank credit institutions and microfinancial activities.” From September 20, 2006. https://cis-legislation.com/document.fwx?rgn=139689

LAW OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN of September 20, 2006 No. ZRU-53 https://cis-legislation.com/document.fwx?rgn=13812

Melnikovová, L., & Havrland, B. (2016). State Ownership of Land in Uzbekistan – an Impediment to Further Agricultural Growth? Agricultura Tropica et Subtropica, 49(1–4), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1515/ats-2016-0001

Mirziyoyevning 100 kuni: “Tovuq iqtisodi” Oʻzbekistonni qayerga olib boradi?”. (2017, March 21). BBC News O’zbek. https://www.bbc.com/uzbek/lotin-39341993

Sabi, M. (2013). Microfinance institution activities in Central Asia: a case study of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Post-Communist Economies, 25(2), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2013.787757

Ranked 75th in the QS World Rankings and 95th in the Times Higher Education 2024 rankings, Lund University is one of the world’s leading universities. Renowned for its interdisciplinary approaches and international co-operation, the university has been an inspiring place for us as researchers and has opened new horizons for academic endeavours.

Ranked 75th in the QS World Rankings and 95th in the Times Higher Education 2024 rankings, Lund University is one of the world’s leading universities. Renowned for its interdisciplinary approaches and international co-operation, the university has been an inspiring place for us as researchers and has opened new horizons for academic endeavours.

Comments