by Farrukh Esanov, guest researcher from the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Uzbekistan

by Farrukh Esanov, guest researcher from the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Uzbekistan

My name is Farrukh Esanov; I am an employee of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Uzbekistan. My secondment at Lund University was held from October 1 to October 31, 2023, within the framework of the project “MOCCA: Multilevel Orders of Corruption in Central Asia”, funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101085855 and coordinated by Lund University, Department of Sociology of Law.

First, I would like to thank the Head of the Department, Isabel Schoultz, Rustamjon Urinboyev, and other project participants for organizing our secondment at a high level, and I also wish them fruitful work!

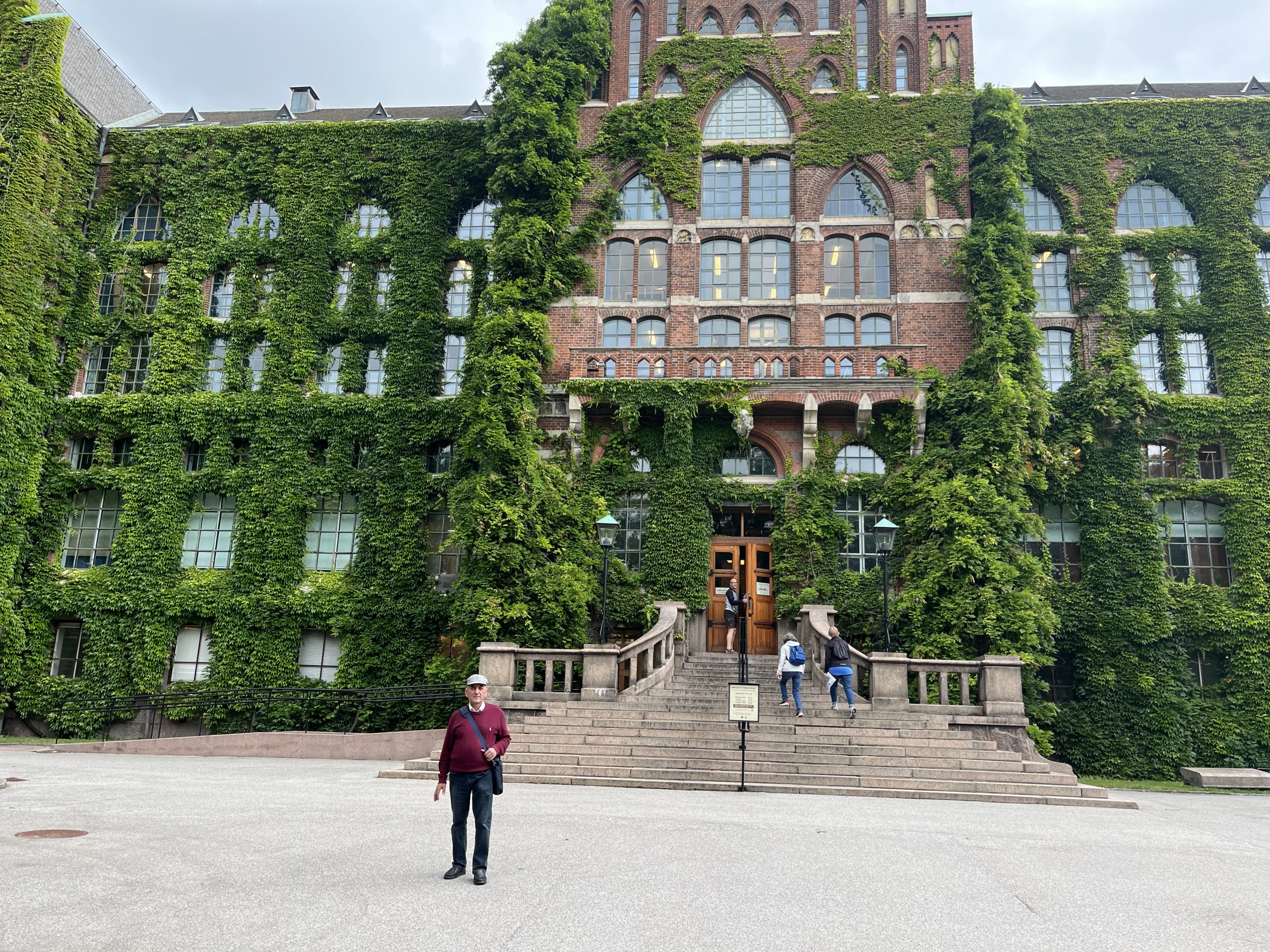

It is a great honour for me and my colleagues to conduct research at such a prestigious university in Sweden.

Doing secondment at Lund University, one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in Europe, provides me with a unique opportunity to enrich my scientific skills and academic experience.

It is essential to mention that Lund University is one of the world’s top universities. The University has approximately 45,000 students and 8,600 staff based in Lund, Helsingborg, Malmö and Ljungbyhed.

Lund is one of the most popular places to study in Sweden. The University has a strong international profile, with partner universities in 75 countries. The university conducts cutting-edge research in various branches of science.

A striking example of the research results is that Anne L’Huillier, professor of atomic physics at Lund University, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. Anne L’Huillier’s was rated at the highest level for her long-term and fruitful work.

Amenities of Lund University

Talking about Lund University it should be especially noted that this university has a multidisciplinary library. In particular, the university has access to EBSCO – an electronic scientific database worldwide.

University staff, students and researchers can access one of Sweden’s most extensive digital libraries. The university’s electronic resources are available through the LUBsearch search system.

LUBsearch is a collective entry point to all the libraries’ joint resources. Through a single search field, you can find articles, journals, doctoral theses and books. Even while away from the university campus, you can access the full texts.

This is one of the advantages of doing secondment at Lund University, which enabled me to freely access and download many articles relevant to my research.

During my secondment, I was able to collect a significant number of articles and other electronic publications on the research topic.

Getting acquainted with these materials gave me a unique understanding of conducting high-quality and meaningful research using new research methods.

According to the Decree of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan, “On the implementation of a qualitatively new system for training qualified personnel in the field of crime investigation”, a scientific and practical legal journal “Investigator of Uzbekistan” has been established at the Law Enforcement Academy of the Republic of Uzbekistan for students, independent applicants and practitioners. Currently, work is underway to gradually include the journal in leading scientific databases (RSCI, DOI, Scopus) to increase its status at the international level, as well as the publication of individual issues of the journal jointly with prestigious legal journals of foreign countries.

My research

The problem of corruption today has become global and systemic. In addition, it has become an insurmountable barrier to socio-economic transformations, as well as state and legal reforms. The consequences of corruption directly or indirectly affect the lives of almost every citizen.

All state legal means and institutions are currently aimed at combating corruption, but the state has not yet achieved a noticeable result for several reasons.

One of the state legal institutions designed to combat corruption in government and management bodies and in the field of economic activity is the prosecutor’s office.

The prosecutor’s office is the entity that must oversee compliance with anti-corruption legislation, as well as the implementation by state and territorial employees of prohibitions and restrictions determined by their service.

The role of a prosecutor’s office in combating corruption is crucial in upholding the rule of law and maintaining the integrity of a country’s institutions. Here are some of the key functions and responsibilities of a prosecutor’s office in this regard:

- Investigation and Prosecution: Prosecutors investigate and bring charges against individuals and entities involved in corrupt activities. They work to gather evidence, build cases, and present them in court.

- Enforcement of Anti-Corruption Laws: Prosecutors enforce the laws and regulations aimed at preventing and punishing corruption. This includes laws related to bribery, embezzlement, money laundering, and other corrupt practices.

- Preventing Impunity: Prosecutors play a vital role in preventing impunity by holding corrupt individuals accountable for their actions. This deters others from engaging in corrupt practices.

- Cooperation with Law Enforcement: Prosecutors often work closely with law enforcement agencies to identify, investigate, and prosecute corruption cases. This collaboration helps in efficiently addressing corruption cases.

- Asset Recovery: Prosecutors may be involved in efforts to recover assets that were acquired through corrupt means. This can involve seizing and returning ill-gotten gains to the state or victims.

- Whistleblower Protection: Some prosecutor’s offices work to protect whistleblowers who report corruption. Encouraging individuals to come forward with information is essential in uncovering corruption.

- International Cooperation: Corruption often transcends borders. Prosecutors may engage in international cooperation and information sharing to combat cross-border corruption effectively.

- Educating the Public: Some prosecutor’s offices engage in public awareness campaigns to educate citizens about the dangers of corruption and the importance of reporting corrupt activities.

- Advising Governments: Prosecutors can provide legal advice to governments on developing and strengthening anti-corruption legislation and policies.

- Ethical Leadership: It’s important for prosecutors to lead by example, demonstrating the highest ethical standards in their work.

Prosecutors play a pivotal role in the fight against corruption, as they act as legal gatekeepers in the justice system. Their actions and decisions can significantly impact the success of anti-corruption efforts and the overall integrity of a country’s institutions.

In addition, the prosecutor’s office is entrusted with several powers to implement administrative enforcement measures for violations of anti-corruption legislation. The Prosecutor’s Office is also vested with important powers to carry out anti-corruption examination of regulatory legal acts and their drafts.

The prosecutor’s office conducts anti-corruption activities based on the new Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan, the Laws “On the Prosecutor’s Office”, “On Combating Corruption”, and other laws.

Corruption as an illegal phenomenon in the sphere of public administration has been known since ancient times. At various stages of its development, almost every state has encountered this problem. In the modern period, we can confidently say that solving the corruption problem is directly related to economic growth and protecting citizens’ rights. It must be admitted that there is no state in the world in which there is no problem of corruption at all, but there are quite a lot of countries where its level is minimal, and therefore, society practically does not feel its negative impact.

As already noted, the entity that can make a very tangible contribution to combating corruption is the prosecutor’s office. The Prosecutor’s Office is the most universal law enforcement agency designed to combat corruption by means of prosecutorial response. Taking into account the fact that the prosecutor’s office can comprehensively influence the causes of corruption and carry out a set of preventive measures in the relevant area, its role in anti-corruption measures increases as anti-corruption legislation develops.

Today, corruption is not associated with bribery; it has quite complex forms of manifestation, which, in addition to its very high latency, represent an increased public danger.

Speaking directly about the legal basis for the activities of the prosecutor’s office in combating corruption, it should be noted that in recent years, the regulatory legal framework in this area has been developing very actively.

In its anti-corruption activities, the prosecutor’s office is guided by the norms of international law, anti-corruption legislation, as well as regulations that come from the Prosecutor General’s Office.

Prosecutor’s supervision is the main activity of the prosecutor’s office; it is through the means of prosecutor’s supervision that various types of offences are identified and prevented, and if there are grounds, the question is raised of bringing guilty individuals and legal entities to the appropriate type of responsibility.

Carrying out prosecutorial supervision over compliance with anti-corruption legislation, prosecutors issue representations, protests, warnings, and decisions.

The Prosecutor’s Office actively participates in law-making activities, which may directly relate to anti-corruption issues. The prosecutor’s office is one of the main subjects of the anti-corruption examination of regulatory and draft regulatory legal acts.

Based on the above, it is clear that the prosecutor’s office is entrusted with a very wide scope of powers to carry out this type of activity, the implementation of which brings certain results.

Thus, the activities of the prosecutor’s office continue to be an effective and still relevant measure to prevent the commission of corruption offences.

Department of Sociology of Law

During my stay at the department, I was very pleased to meet with the head of the department Isabel Schoultz and Professor Anna Lundberg. Everyone in the department welcomed us warmly.

The Department of Sociology of Law has created all necessary conditions for researchers.

About Sweden in general

Sweden is one of the most developed countries in Europe. Sweden ranks 4th in the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index, 5th in the Corruption Perceptions Index and 6th in the 2023 World Happiness Index. Here, the values of people’s lives are given special importance.

Lund is one of the oldest cities located in southern Sweden, which is also known as a student city. A small, cosy and very green city was founded at the end of the 10th century.

Lund is also located in Skåne, or Scania, a southern Swedish region with magnificent nature and rich agricultural traditions.

Lund is a regional centre for high-tech companies. Companies with offices in Lund include Sony Mobile Communications, Ericsson, Arm Holdings and Microsoft. Other important industries in the community include pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, publishing and library services.

Summing up, during my secondment, I was given the opportunity to use Lund University’s electronic resource database, exchange views with project participants who shared invaluable ideas on how to conduct research using different methods and achieve my research goals. Most importantly, I gained insight into new research methods that will be useful for my future research activities. Thus, this project provided a unique path to further expand my knowledge in the relevant field.

In particular, I became familiar with the practice of conducting research on problems arising in practice and considering the issue of introducing appropriate changes to legislation based on the results of these studies.

In conclusion, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the Department of Sociology of Law at Lund University and the project “MOCCA: Multilevel Orders of Corruption in Central Asia” for the excellent organization of my secondment.

Lund University holds a high rank in international comparisons of higher education institutions, consistently placing in the global top 100 in various university rankings. Conducting research at this esteemed university was a delightful experience for me.

Lund University holds a high rank in international comparisons of higher education institutions, consistently placing in the global top 100 in various university rankings. Conducting research at this esteemed university was a delightful experience for me. I began reading books recommended by the professors in my department, gaining insights into the origins of corruption and research methodologies for studying it.

I began reading books recommended by the professors in my department, gaining insights into the origins of corruption and research methodologies for studying it. My research at Lund University focused on the topic “Prospects of improving the legal framework of the Republic of Uzbekistan related to foreign direct investments and issues of reducing the risk of corruption.” During this research, I examined the mechanisms for safeguarding the rights of foreign investors and investigated the historical and current legislative measures implemented by different countries to combat corruption in this domain. Working alongside leading professors and teachers at Lund University, I collaborated on drafting an article within the scope of my research topic. The studies revealed that developed countries follow certain practices to protect the rights and legal interests of foreign investors and prevent corruption in this field:

My research at Lund University focused on the topic “Prospects of improving the legal framework of the Republic of Uzbekistan related to foreign direct investments and issues of reducing the risk of corruption.” During this research, I examined the mechanisms for safeguarding the rights of foreign investors and investigated the historical and current legislative measures implemented by different countries to combat corruption in this domain. Working alongside leading professors and teachers at Lund University, I collaborated on drafting an article within the scope of my research topic. The studies revealed that developed countries follow certain practices to protect the rights and legal interests of foreign investors and prevent corruption in this field:

by Farrukh Esanov, guest researcher from the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Uzbekistan

by Farrukh Esanov, guest researcher from the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Uzbekistan

Comments